Family Matters:

A History of Baláy Dakû

(Big House)

Jan Philippe V. Carpio

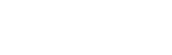

Girl of my Dreams, Citation in the Full-length Category, 2001

Balay Daku, Finalist in the Full-length Category, 2003

Context

Baláy Dakû is the first Ilonggo digital full-length feature film, created as a response to the economic and imaginative hegemony of the Metro Manila film industry. Apart from a brief renaissance of the Cebuano film industry in the 1970s, the Metro Manila film industry has held sway over the hearts and minds of Filipinos. Its only main competition – and fittingly, its main conqueror – has been Hollywood.

Similar to Hollywood’s lack of diverse depictions of American life, the Metro Manila film industry has its own monolithic depictions of so-called Philippine culture in mass media. Its commercial narrative filmmaking forms tend to focus on homogenized, simplistic, relatable-to-all stories. What can be lost in the storytelling, as well as the filters of the entertainment industry, are authentic depictions of diverse and multilayered Philippine lives. One example of a stereotype perpetuated by the industry and bemoaned by my late father is the depiction of a character from the Visayas as a naïve, gullible, maid in an affluent Tagalog household. What may seem like harmless entertainment, unless given proper context and reflection, can encourage certain kinds of mindsets and biases. I feel that reinforcing stereotypes and cliches are a kind of violence—a passive kind of violence, a violence of omission, a violence of distortion, but violence nonetheless. This might seem like an exaggeration, but one cannot deny that there is something wrong when one culture reduces another to mere comedic relief.

Development

Levi Marcelo and Astrid Tobias were my batchmates from National Artist Ricky Lee’s 11th Scriptwriting Workshop in 1999. Levi was very encouraging about my dream to make an Ilonggo film. By 2001 we were already collaborating to make the film with a film grant from the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA). Levi would co-produce the film. Astrid would co-write the screenplay. She also suggested casting her schoolmate Banaue Miclat in the lead role of Stella. Despite our lack of experience in producing films, we were buoyed by the optimism and enthusiasm of our youth. Ignorance was also a great ally. To quote John Cassavetes, “Sometimes it helps not to know what can’t be done.”

Without digital video advancements becoming affordable, the chances of making a full-length Ilonggo film on celluloid – even in 2024 – would still be slim to none. Activist and writer Dino Manrique also introduced me to the work of Cassavetes which provided monumental inspiration and guidance.

It was not enough to just make a film where the characters spoke the Ilonggo language. The form and style of the film needed to embody my own deeply personal experiences of growing up with my family and friends in my hometown of Bacolod City, Negros Occidental.

Pre-production

With the film screenplay-in-progress and the film grant application submitted, pre-production proceeded months before a tentative 2002 summer film shoot. Our Ricky Lee workshop batchmate from Mowelfund, Bahaghari, agreed to be the cinematographer. Batchmate Job Pagsibigan lent his DSLR camera as a prop for Stella. A CCP film workshop classmate, Grig Montegrande, agreed to rent out his digital video camera and microphone.

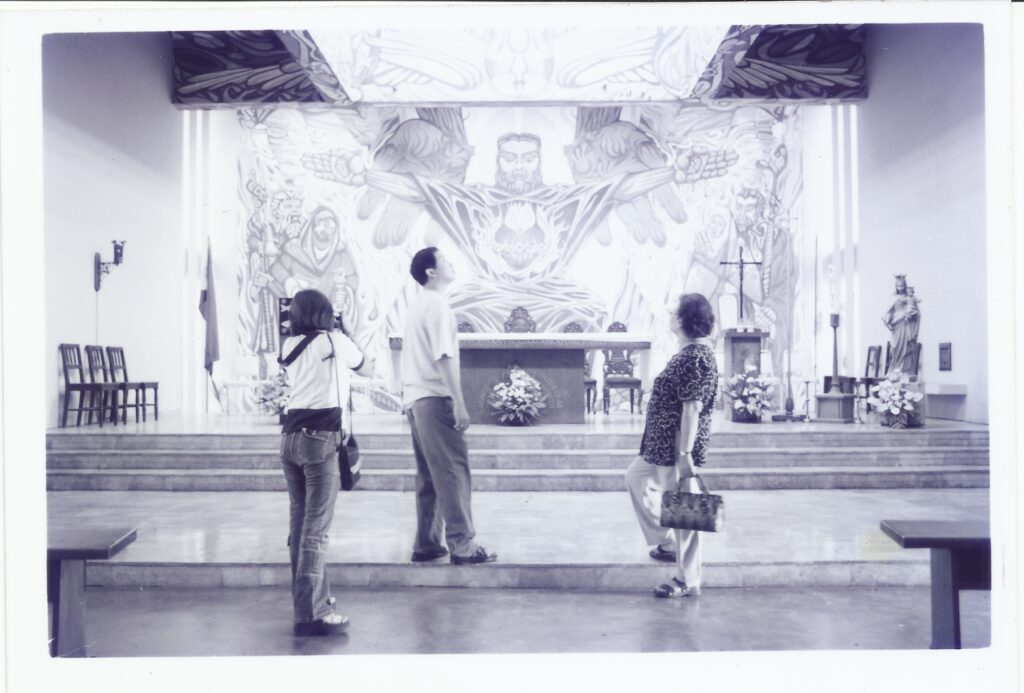

My family and our household staff helped me obtain the initial shooting and location permits. My mother’s family would provide lodging for Bahaghari. My godfather Felix “Boy” Suarez agreed to let us use his family’s ancestral home as the main location. The Suarez home’s long history, architecture, space, and appearance became crucial in providing more authentic layers of emotional and psychological atmosphere for the film.

The City of Bacolod, the Negros Cultural Foundation, the University of St. La Salle Bacolod officials, which included acclaimed Bacolod artists, writer Elsie Coscolluela, and film director Peque Gallaga gave their support to the project. Tanya Lopez, head of the theater program, recommended local actors who would best play the Gonzalez family in the film. They were Mandy Alimon for the role of the younger son Julio, Dennis Ascalon for the older brother Boy, and Tita Lindy Osmeña for the matriarch Inday Carmen. I met with actors who all gave their commitment for our film shoot. The roles of Julio’s childhood sweetheart Isabela, played by Riega Dioneo, and the maid Lore, played by Nadjah Lee Española, were cast through an audition held at La Salle Bacolod. Minor character roles like the pedestrian played by Tyrel Storm Gamboa (Assistant Director), were also cast. The actors agreed to provide their own clothes for their characters.

The film revolves around the inner lives of a family of sugar hacienderos. My late father came up with the film’s title. My father told me that the sugar farm workers refer to the haciendero family home as Baláy Dakû. The literal English translation of the title “big house” refers to the size of the house owned by a wealthy family. “Big house” is also an American idiomatic expression meaning prison— a fitting metaphor for the emotional and societal prisons the film’s characters were trapped in.

Bahaghari borrowed Grig’s video camera two weeks prior to the shoot so he could practice with it. By the time the shoot started, the camera had become an extension of his eyes, hands, and body. We both agreed that the film would be shot with mostly available light – while occasionally boosting the existing light sources with improvised film lighting.

Everything seemed set and ready for the shoot. I then learned that the best plans can change. A filmmaker must be able to discern if a plan is changing for the worse or for the better. Due to schedule conflicts, two actors, Miclat and Ascalon, backed out just a short time before the shoot. The NCCA grant would not be approved in time for the shoot. The screenplay was half-completed. Pepper told me that he and Astrid would not be joining me for the shoot. That bothered me because I was feeling quite inexperienced and insecure that I would be able to pull off directing the film without a support group.

I was too immature to realize that perhaps one of the worst things that could happen is for a shoot to go completely smoothly without a hitch. Without any challenges and problems, one will not learn how to deal with them when they eventually come. Challenges and problems are essential parts of an artist’s creative process and growth.

My parents helped me raise the film’s very modest production budget of around P80,000 through donations from generous relatives. These were to be reimbursed if the grant was ever approved. My family and our household staff became my support group during film production.

Bacolod’s Department of Tourism Secretary Imogene S. Kana-an’s important contribution was introducing me to Miclat’s replacement, her co-faculty member at La Consolacion College Bacolod, Joy Veniegas Ramirez. Ms. Kana-an primarily recommended Joy because she had actually experienced the story of her film character in her own life.

When I met Joy at a local restaurant near my home, I admit I was skeptical then if she could handle the role. I was very wrong. Joy’s painful life experiences along with her skills as an actor enriched her performance in ways that I only appreciated years later.

Joy then introduced me to Ascalon’s replacement, one of her former theater students, Glynn Medina. Glynn lived in La Carlota, a city located in the Southern central part of Negros. The first time I saw Glynn, he had his injured right arm in a sling, sitting behind his friend driving a motorcycle up the La Salle Bacolod driveway. I thought to myself then, “This has to be the guy to play Boy. He’s already agreed to join the shoot. He’s injured, but he rode a motorcycle over a hundred kilometers to meet me and Joy.”

With the final cast in place, Tanya Lopez put the actors through a short series of workshops to prepare them for the film. Observing Tanya’s process and the acting fruits they bore during the shoot would teach me the importance of actors’ preparation. This would influence my own working process with actors for all my future film projects.

Tanya’s process focused on character histories, characters’ relationships with each other, and characters’ relationships with their living spaces. She had each actor familiarize themselves with their character’s room and space in the Suarez home. Actors acted out improvised scenes with each other based on their characters’ pasts. These scenes would aid in creating imaginative foundations for their relationships in the film. In my own Bacolod bedroom, Tanya, Joy, and Mandy worked together with trust and touch exercises to make them both physically comfortable and intimate with each other since they were playing a married couple.

Production

The main shooting location was the Suarez family home, with other locations around Bacolod and Silay City. The challenge was how to make the people, the environment, and the spaces express the narrative, and not turn the film into a tourism travelogue.

Instead of the strict, corporate hierarchies of commercial film shoots, Baláy Dakû became a familial experience. My family and household staff provided the day-to-day administrative and logistical support. I trusted Bahaghari with the film’s visual interpretation while I focused on the screenplay and the actors. Some of the cast members doubled as crew members like Riega who was a production assistant and Glynn who was a make-up artist. The camaraderie among cast members was jovial and supportive. My former high school English teacher, Mrs. Rosana Gaspay, even joined the shoot as a make-up artist. My parents, relatives, and friends were cast as extras in the birthday party scene. Workers from our family and relative’s farms were cast in farm scenes. Meals were served to the cast and crew on time. An honorarium and travel allowance were paid to each actor. With some exceptions, shooting usually began at 9 AM and ended by 7 PM.

The film was shot over eleven days in April 2002. During the film’s production, an important reference and source of inspiration for film directing was Professor Ray Carney’s biography of John Cassavetes. The book got me very interested in the most overlooked part of filmmaking: directing actors. Hollywood actor turned film director John Cassavetes is considered the patron saint of independent filmmaking. He was also a master actors’ director who came up with his own unique and inimitable methods to direct actors. The acting performances in his films are frighteningly intense, singular and unpredictable compared to majority of other films. I was inspired by him to begin exploring my own methods of working with actors and pushing the boundaries of their performances.

To address the unfinished screenplay, risky techniques pioneered also by Cassavetes and Andrei Tarkovsky were adopted. I chose to use the unfinished screenplay as a foundation, and write the rest of it as we shot the film. I would give the scenes to the actors as we went along, and as much as possible, shoot the film in sequence.

Shooting in sequence is generally not practiced and is quite impractical. These techniques at their worst can create a haphazard and scatterbrained film. At their best, the improvisational nature of the writing and the shooting would keep the narrative spontaneous, fresh, and alive for both the actors and the crew. Mostly shooting in sequence would allow the actors a more organic and authentic process to grow their characters.

My father pointed out that since English was my first language, my writing in Ilonggo might be limited and awkward. So, he suggested to allow the actors the freedom not to stick to the script all the time. When the actors felt it was needed, they would say their lines based on their interpretation of their characters. Significant parts of the natural, spontaneous behavior and feelings in the film were generated through this method.

The Cassavetes biography did not have a step-by-step guide on how to direct actors. That information was anecdotal. So, working with the Baláy Dakû cast was an on-the-job learning process for me. I first worked on gaining the actors’ trust and respect which are the most crucial elements in any working relationship. I did not let my insecurities affect my professionalism towards the actors. Another crucial factor was that the veteran actors did not take advantage of me. They treated me as an equal. We developed a relationship of mutual trust and openness. The most convincing example of this was my relationship with Mandy Alimon (Julio). Mandy was my high school algebra teacher in La Salle Bacolod. Before we started shooting, I kept calling him “Sir Mandy” because I was used to calling him that as my teacher. He told me to stop calling him “sir”, which puzzled me then. I only realized later on that as an experienced, veteran actor, Mandy knew that if I kept calling him sir, the feeling of me being his former student and subordinate, would subconsciously prevent me from directing him freely. Another example was when Mandy and Joy were uncomfortable about shooting a sex scene. Both of them were teachers so limits needed to be imposed in the scene. Bahaghari and I sought their approval for specific details in the scene. We collaborated with them to make sure they were comfortable with what they were doing.

I adopted Cassavetes’ principle that actors, just like your crew members, are equal collaborators in realizing the film. Instead of shooting for coverage or following a storyboard, we filmed scenes mostly using long takes. This method helps actors’ emotions, responses and behavior grow organically. The common practice of breaking a scene into several shots tends to stifle the natural flow of the actors’ performances. Instead of looking for “perfect takes”, we adopted Cassavetes’ methods of using multiple takes as rehearsal time for the scenes, as well as exploring different and more complex emotional variations of performing the scenes. The long takes also made the audience experience the slower pace of life in a provincial city like Bacolod.

The scenes were prepared for, but not strictly predetermined. I realized while making Baláy Dakû that witnessing talented, skillful, and brave actors bringing a film’s scenes to life gave me great pleasure. I was very fortunate to have such a talented and excellent ensemble with almost effortless chemistry. Most of the principal actors also had a talent for improvisation which was crucial in creating the characters’ emotional and behavioral variations for the different takes. These methods created genuine moments of spontaneity and surprise for myself and even the actors. As D.H. Lawrence once said, “No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.”

The shooting style was a response to the slick, formulaic cinematography of mainstream film production. Borrowing from Cassavetes’ and Dogme 95 methods, the camera and the lighting would be subordinate to the actors. The ephemerality of the actor’s art form requires periods of stimulation, activity and rest. The glacial pace of industrial cinematography methods tends to kill the actors’ performances with a lot of waiting around. Fast camera and lighting set-ups – made even more possible with the portable digital technology then – would help keep the actors’ performances fresh and alive. We shot this fiction film like we were shooting a documentary: exploratory but also deliberate, naturalistic but sometimes expressionistic. We were all responsive to what was happening in front of the camera and sometimes even behind it.

A creative process ritual was also established during the shooting of this film that would be consistently repeated throughout my subsequent films. The first few days of shooting usually seem to be all about the cast, crew, and the film itself, feeling each other out. I scheduled physically intimate scenes between Joy and Mandy on the first day of shooting. We learned that day that the two actors would need more time to become more physically comfortable with each other. Their day one scenes were rescheduled for reshooting, and the day one footage was scrapped.

All these shooting experiences, methods, and techniques converged during the last few days of shooting. There was a crucial reckoning scene between Isabela (Riega) and Julio (Mandy) to be shot. It was a crying scene and I had never directed a crying scene before. I did not know how to get Riega to cry. I have heard stories where directors tend to rely on trite methods where they play sad music to make the actor artificially sad or even abusive methods where they curse the actors out or even physically hurt them. Even the filmmaker I admire the most John Cassavetes was not above using abusive directing methods. I refused to be either trite or abusive, so I went into the shooting the scene with no idea what to do.

Just before we shot the scene at the terrace of my family home, I took Riega into my bedroom. We both sat down on the floor in silence. We did not say a word to each other. I was wracking my brain how to direct her to cry in the scene. The next moment, something spontaneous happened. I just kept repeating a line over and over again. “I don’t know what to do … I don’t know what to do …” Tears started filling my eyes. I was crying. Not before long, Riega also started crying next to me. We cried together for a few minutes. Then I stood up and said, “Okay, let’s shoot the scene.” Riega’s performance in the scene was quietly painful and beautiful. I would later call this technique “empathetic direction” and use it in different variations in subsequent films.

Since I was writing half the script as we filmed, I did not have the film’s ending. This creative problem was made more urgent by Bahaghari telling me that he needed to leave for Manila for another shoot by the middle of April. To paraphrase the lines used to describe Cassavetes’s films: I did not need the film’s ending. I needed the moment when the film stops. The solution to the problem presented itself to me on the second-to-the-last day of the shoot. Bahaghari took a group photo of cast and crew. He played a photographer’s prank on us which gave me the idea for the film’s final shot.

While filming the climactic dinner scene on the second-to-the-last-evening of the shoot, I noticed something with Joy. Her acting interpretation of Stella’s behavior was not the same as the direction I gave her. Instead of cutting the takes and correcting her, I respected her interpretation. There were two reasons why I did not say “cut”. The first reason was that while Joy’s interpretation of the character at that moment was not the same as mine, it did not feel wrong. It was just different. The second reason was a lesson learned from the Cassavetes biography where he encountered a similar situation with his wife and lead actress Gena Rowlands during the filming of a A Woman Under the Influence. If a director and an actor do not agree about the interpretation of a character, the actor might be wrong, but the director has to be open to the possibility that the actor might have a deeper interpretation of that character. This was the case with both Rowlands and Joy. I only realized later on that Joy’s performance in that intense scene was painfully drawn from her own real life, her own personal experiences. Her courage and her skill added incalculable emotional layers to the scene.

Post-production

After we completed shooting, I stayed in Negros for a few more weeks to further bond with the cast and to log all the fifteen hours of footage we shot. The NCCA grant was finally approved on April 16 and used for reimbursement. In hindsight, the NCCA must find a balance between bureaucracy and meeting the needs of its approved applicants. If we had waited for the grant before we began shooting, we would have never been able to shoot the film.

Upon returning to Manila, I was aching to edit the footage. Pepper told me to wait for a few more weeks before beginning editing in May. I did not appreciate his wisdom at the time of allowing the footage and myself to breathe so that I could look at it with fresh eyes. Since I was both the film’s director and co-editor, Pepper knew that a rest period was needed so that I could make creative editing choices with less bias.

I edited the film on Pepper’s computer for two months straight. He helped instill discipline by creating a work system. From Monday to Saturday, I would take the then newly constructed MRT train from Makati to North Avenue station. I would walk from the station while carrying the camera and the tapes to Pepper’s apartment at UP Bliss right behind SM North EDSA. I would edit from 9 AM to 6 PM, with meal breaks. I would go home after dinner. He would never let me continue editing after dinner even if I wanted to. This discipline kept the motivation and momentum going for the next day’s work.

Pepper and his mother Emily Marcelo provided their home and the equipment. He provided a lot of moral support and much-needed frank feedback on the scenes and the different cuts. Pepper generously did not charge me for the editing. He only wanted an executive producer credit on the film and for it to be a co-production of our mentor Ricky Lee’s Writers’ Studio.

This was my first time editing my own film on a nonlinear editing system. The technology was still fairly new. In this case, it was Digital 8, a transition format from analog Video 8. DV in its standard and high-definition variants would eventually become the dominant format for most of the 2000s. Unlike the card, hard disk, and cloud-based cameras of the present, old digital video cameras still used analog magnetic tape to store the digital footage. The firewire cable and video capture card were used to “capture” (transfer) the footage in real time between the camera or player and the computer. Unlike the faster, high-speed transfer of video files with today’s technology, real time meant if your total raw footage was 15 hours, it would take fifteen hours to digitally transfer and store all of it. The older video codecs also took up more hard drive space. With limited time, hard drive space and computer processing power, meticulously logging your footage became even more essential.

The film’s more-than-three-hour running time came out of a deliberate editing process. Since the film’s scenes were shot mostly in one, long take, editing became a matter of balancing the length of the take, the visual energy of the image, the authenticity of the acting performances, and how the take’s individual rhythm fit in with the overall pace and rhythm of the entire film. If a scene with a long take could not individually sustain itself, it was not considered for the film’s assembly. When it felt necessary, jump cuts were used to break up the long takes. The jump cuts were not used to condense cinematic time and space as was common practice. They were primarily used to emphasize the emotional shifts of characters in a scene. Emotional unpredictability and authenticity were placed above visual continuity. Instead of narrative clarity, spontaneity and narrative openness were the goals.

An equally important element was the Baláy Dakû sound design. We did not have professional sound equipment. We relied solely on the microphone accessory mounted on top of the camera. The sound was not of professional quality, but was adequate for our needs since we could control the noise levels in most of the locations. Two of the most important decisions for the sound design were having no musical score and not cleaning up the ambient sounds recorded with the shots. I did not want to overly manipulate and spoonfeed the audience with music. I wanted the audience to make their own emotional decisions and judgments regarding the characters and the narrative. I wanted to push the illusion that this actually happened, and the camera just happened to be there to record it. Borrowing from Dogme 95, the only scene with music was when one character was singing a song to another. In many moments in the film, the ambient sound replaced the need for the musical score. Unlike most commercial films that tend to have their actors dub their dialogue tracks and completely scrub clean the ambient sound track, I noticed that the ambient sound in many different shots helped add to the film’s overall psychological atmosphere and tone. I realized that cleaning up the ambient sound too much or even a little would take away from film’s overall mood and tone. For example, in the climactic dinner scene, the ambient evening sounds and even the camera and microphone noise helped heighten the already present emotional tension in the scene. Another example was a spontaneous moment when the dogs belonging to my godfather howled in chorus at just the right moment during a scene in the house’s eerie and mysterious second floor.

Distribution

After the film’s post-production was completed, the master copy needed to be digitally copied on three Digital 8 tapes and three Mini DV tapes. The film’s screening copy was on two VHS tapes. Several copies of the film that I sold later on were on three VCD discs.

Shane Escueta did the accounting for the film. We submitted all the required NCCA documents to complete the project. Around Php 8,000 of the Php 90,000 grant was unused, so we returned that to the NCCA as well.

The film’s premiere was at the NCCA theater in Intramuros. This was pre-social media so the film’s marketing was done through telephone, SMS, e-mail, and internet forums. The film did not fit the mainstream narrative mold, but the response to the film was generally positive. After the screening, acclaimed film director Jeffrey Jeturian even sent some encouraging feedback and praise through a text message.

In stark contrast, the screenings in Bacolod garnered mixed responses. At my alma mater La Salle Bacolod there was indifference, bewilderment, and some outright hostility from some audience members. At Joy’s La Consolacion College class screening there were more open emotional responses to the film. One in particular I remember was a male student who was constantly laughing and mocking Glynn Medina’s character Boy. As the film progressed, he begrudgingly admitted to his female classmate that Boy’s behavior was an honest depiction of some men. The most visceral responses from the film came from friends and family who would borrow a copy of the film to watch in their homes. Surprisingly, many older women completely detested Joy’s character Stella because they were relating her story in the film to something quite similar in their own personal lives. The best reactions affirmed the authentic depiction of the inner lives of a Negros landed family.

The NCCA and Bacolod screenings would prove to be the median pattern of the film’s reception with audiences and critics— that is, ranging from enthusiastic praise to complete indifference and dismissal. With a few exceptions, the cast was universally praised for their naturalness, skills, and abilities. Even though the negative criticism was discouraging at times, I could generally take it. The film obviously has its flaws, but I feel that the good things in the film do outweigh those flaws. I would only react defensively when someone failed to recognize the acting prowess of the cast. My father also reminded me that by choosing to make a film outside mainstream forms, I should expect those kinds of reactions.

During a reunion with some of the cast members, Mandy revealed to me that sometime after the film’s premiere, he ran into his mentor, acclaimed actor and Bacolod native Joel Torre. Joel asked him if he had had a romantic relationship with Joy during the shoot. Mandy answered no. Mr. Torre’s question was a testament to Mandy and Joy’s believability and authenticity as a married couple.

Baláy Dakû’s first film festival screening was at the 3rd Eksperimento Film and Video Festival (26 February – 1 March 2003). It was also screened at the 16th Gawad CCP Para sa Alternatibong Pelikula at Video (14 February 2003), where it was awarded a special citation. Other screenings were at the 1st Baguio Independent and Alternative Film and Video Festival (September 2003), .MOV International Digital Film Festival, Cebu City (March 2005), 1st Cinemalaya Philippine Independent Film Festival (July 2005), 3rd Cinemalaya Philippine Independent Film Festival (July 2007).

The film had only one more screening tour from 2015 to 2016 at the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) Baguio, Iloilo, and Davao Cinematheques.

The most unpleasant screening experience occurred at Pelikula at Lipunan Festival in Iloilo City (February 2004). I had sent one screening copy of the film that consisted of two VHS tapes. The organizers for some reason made the huge mistake of not programming enough screening time for our three-hour plus film. Three of the main cast members – Joy (Stella), Tita Lindy (Inday Carmen), Riega (Isabela) – were present at the disastrous screening. According to them, there were technical problems screening the first tape – dirty tape head playback and audio dropouts – before the organizers abruptly stopped our film’s unfinished screening altogether to make way for the next film scheduled. I was obviously quite angered by this incident. Apologies were made to me over the phone by one of the festival’s organizers, but to this day, I have always called into question their behavior and professionalism during this incident.

The Pelikula at Lipunan screening fiasco taught me the importance of screening films with sensitivity and care, and the particular attention needed in screening a film longer than three hours. For public screenings, the affordability of the screening media was sometimes outweighed by the poor quality of VHS and the playback unreliability of VCD and DVD. For subsequent screenings, I would screen the films mostly using Mini DV playback.

So far, the film has not been able to find a wider audience even among Ilonggos. Since 2002, several cast and crew members have sadly, prematurely died: co-writer Astrid Tobias, youngest cast member Nadjah Lee Española (Lore), my father Sonny Carpio, and lead actress Joy Veniegas (Stella). The experiences of making and screening the film together have run a gamut of emotions.

As we prepare for the film’s 25th anniversary in 2027, I continue to lean on the hope of our film and other films that attempt to honestly portray not just a people and their language, but the myriad ways people can see, think, and feel about life.

Gawad CCP para sa Alternatibong Pelikula at Video, or Gawad Alternatibo for short, is the longest-running independent short film festival in Southeast Asia.

quick links

Contact Info

- Roxas Boulevard, Pasay City, 1003 Metro Manila

- Tue-Fri 9am-6pm

join our Newsletter

Sign up for our newsletter to get updates.