If the World and Waters Permit:

On Gipaambit (2021)

Anna Miguel Cervantes

Mga Gipaambit Gikan sa Tubig, 3rd place in the Documentary Category, 2021

Forces of fragility

The travel to Camp Bilal in Lanao del Norte was scenic. When we arrived, a man in a black shirt bearing the acronym BIAF (Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces) showed us around. It was an expansive space, dotted with unpainted structures that were only recently completed. The masjid was large and airy with doors perpetually open. There was a concrete stage facing nothing in particular at that time, but it hoped to gather hundreds of warm bodies no longer for battle, but for peace and development.

It took us an hour to travel from Iligan City to the Municipality of Munai where Bilal(1) was located. Due to the precarious state of peace in that part of Mindanao(2) in the past decades, I’d grown accustomed to security forces in checkpoints spread over the region. Passengers were told to exit the vehicle, show our IDs and the insides of our bags. Most of the time, they let us pass with no mind. It has been like this since I was a child.

I was with a small team from Pakigdait, Inc., an interfaith peacebuilding civil society organization that had built rapport with the community inside the former rebel camp. This included its leader, Abdullah ‘Commander Bravo’ Macapaar. He is the Northwestern Mindanao Front Commander of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). He is also currently Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) Member of Parliament. From fighter to legislator. I’d met him in brief increments and known him to be wholly dedicated to this chapter of peaceful transformation.

The BIAF is the armed wing of the MILF, a revolutionary organization that once declared war on the national government for its systematic failure to attend to developmental needs and rectify historical injustices of the Bangsamoro-dominated region in Mindanao. Between the national government and the MILF, the armed conflict caused destruction and countless casualties on all fronts that lasted for more than two decades.

On that day, I was in Camp Bilal for an ocular visit to shoot a film and conduct an art initiative funded by British Council Philippines. The date was 11 March 2020(3). Unknown to us, there were much larger forces of discord already being waged elsewhere.

The intended film did not materialize. Pre-production was slated that week, 11-21 March 2020. It was difficult to leave, knowing I’d also leave a dream behind. But when whispers of a city-wide lockdown became imminent, I had to decide sooner than later. I eventually exited safely from Iligan to Davao within 48 hours of the ocular.

By 15 March 2020, everything proved fragile. The veil that covered the entire world proved to be unyielding, and everything became like sand pillars caving in.

Under the Comprehensive Agreement of the Bangsamoro (CAB), Camp Bilal is one of the six recognized camps of the MILF. Thus, Camp Bilal is a government-acknowledged MILF Camp.

The island of Mindanao in the Philippines has been a battleground for intersecting conflicts. In those centuries birthed the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and later the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) that have fought for the self-determination of Muslim Mindanao against the Philippine Government. After seventeen years of negotiations, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was established.

March 11, 2020 was the same day former president Rodrigo Duterte would tell the entire nation that we were fools who were “too scared of this coronavirus epidemic.” Only a day after, on 12 March 2020, Metro Manila was placed under lockdown in an attempt to stop the spread of the then-mysterious virus. This crass, flip-flopping tirade would continue on for long. Quote from: https://www.cfr.org/blog/philippines-rodrigo-dutertes-response

Ways of seeing

I scoured through hundreds of media files for Mga Gipaambit Gikan sa Tubig (Whispers from the Waters of Mindanao)— sound files, photos and videos shot on an iPhone 7 or a first-generation iPhone SE. Only the epilogue contained footage from a cinematic camera, a Sony A7SII. During fieldwork, I found smartphones to be largely unobtrusive. The trickle down of technology has penetrated even the deepest hinterlands, which meant touchscreen phones capable of recording video were commonplace. I consider Gipaambit a smartphone film.

Many shots were happenstance, just enough seconds of an iPhone live photo to be recognized by an editing machine as a short clip. Several clips were never meant to become a part of moving images, but upon rediscovery, I found the additional frames like secrets unearthed. It was a great experience to review years of footage from travels around Mindanao, most of them seen for the first time since recording. Complete isolation during the pandemic afforded me the time.

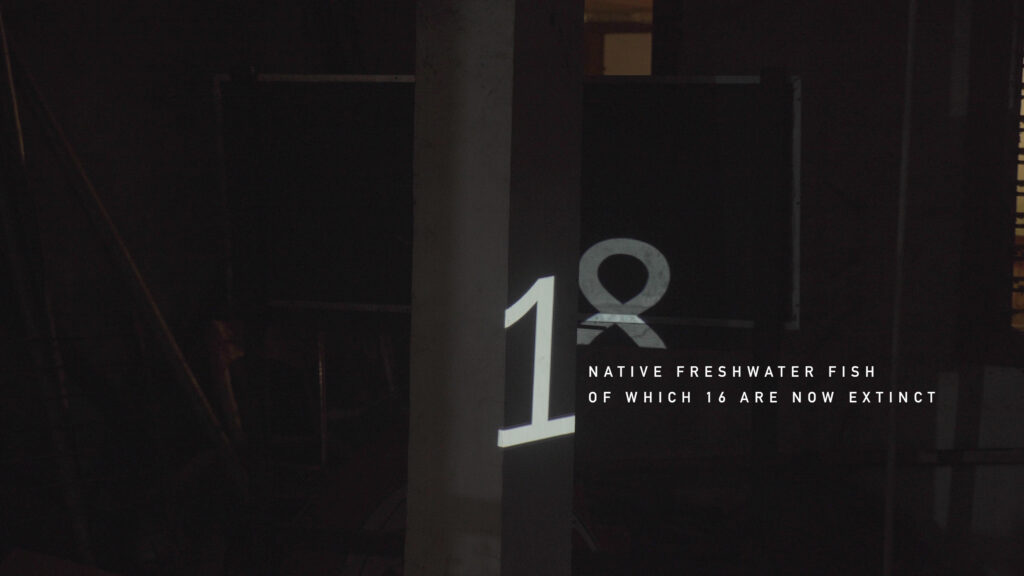

Conceptualization for Gipaambit felt instinctual. Gestalt. If asked which came first— the dialogue and narrative or the flow of images?— I couldn’t say for sure. Both sound and video informed each other to become more than their individual parts. But the core of the work lies in my belief that in armed conflict, the least noticed effects are its impact on natural resources—the land, bodies of water, animals, insects, and other unseen spiritual creatures that live within them. Its entry point is through the retelling by a Mindanawon historian of the origins of the 2017 Marawi siege, its myths, and the new narrative that is written when truth and the unknown converge.

Then I got to writing. There’s a fine line to walk as an artist who attempts to tell a story much larger than themselves. It’s prone to intrusion, self-centered propaganda, and other factors that become problematic. I approached the story with respect and an awareness that I was a third-party outsider looking in—within the bubble of safety, often inside a vehicle, coddled by bureaucracy that somehow afforded me protection.

Gipaambit is my second film, the second film I edited, and my first documentary. It has been screened in artist-run spaces like BARAKS in Quezon City and Emerging Islands in La Union, both set up like warm homes. More than public or online screenings with wider audiences, I felt it was important to be able to open discussions between individuals who are unaware of the ongoing BARMM peace process. This is where my work transcends filmmaking to become that of peacebuilding. Above all else, I wish for Gipaambit to be a point of discourse.

River flows back

March 16, 2024—Commander Bravo remains patient. He stands alongside his supporters who want to take photos with him inside the historic Camp Bilal. It’s been four years since I last visited, and so much has changed. They’ve built health centers and expanded original structures. We were there to retrieve 200 packs of relief goods following two communities with deadly encounters in the previous weeks. Peace spoilers, as they say, still remain.

My original thesis for Gipaambit was that all wars destroy nature. But on the way to Lininding, Munai, Lanao del Norte, this was not the case. We passed by the most beautiful terrain I’d ever witnessed in my entire existence. Vast stretches of untouched forests, clear flowing rivers, ecological diversity, the songs of creatures and critters. There’s a powerful force protecting these lands unlike any of us.

This must be on the way to a certain heaven, I thought during the entire trip. Perhaps another retelling will be in order, if the world and the waters permit.

Gawad CCP para sa Alternatibong Pelikula at Video, or Gawad Alternatibo for short, is the longest-running independent short film festival in Southeast Asia.

quick links

Contact Info

- Roxas Boulevard, Pasay City, 1003 Metro Manila

- Tue-Fri 9am-6pm

join our Newsletter

Sign up for our newsletter to get updates.